Nestled among eucalyptus trees in North San Diego County, the historic Rancho Santa Fe is known for its golf courses and palatial estates. It is one of the most exclusive and expensive postal codes in the United States.

The approximately 10 square mile enclave is one of California’s oldest planned communities – officially established in 1927 as a haven for Hollywood royalty and other 1 percent stake in that era.

At the center of its creation was the Rancho Santa Fe Protective Covenant, which was passed in 1928 and enacted both architectural and racial restrictions to ensure it would be a whites-only paradise.

The covenant read:

“No part of this property may be sold, transferred, rented or leased, in whole or in part, to any person of any African or Asian race, or to any person who is not of the White or Caucasian race.”

The racial restrictions were finally removed from the document in 1973, more than two decades after they were banned by the US Supreme Court. But the Rancho Santa Fe Protection Treaty is still the most important document of the community. And although the outwardly racist language has disappeared, the connotations remain.

“What is unique about Rancho Santa Fe’s contract is that it not only restricted the deed itself to whom a seller could sell, but also restricted a variety of activities or even types of architecture,” Phoebe Young, author of “California Vieja,” “By combining both racial restrictions with architectural restrictions, I think it’s quite unique at the time.”

Cristina Kim

A statue of the master architect of Rancho Santa Fe, Lilian Rice, November 13, 2021.

Built on a myth

The Spanish colonial architecture of Rancho Santa Fe, known for its arches, adobe bricks, and red tile roofs, is rooted in a white fantasy of California’s past, according to Young and other historians.

“It was an idealization of a particular era that ironically seemed to build on both the indigenous and Mexican history of the region, but in a way that served to exclude the contemporary – that is, in the 1920s – residents who themselves Indigenous, Mexican Americans, or Mexican nationals, ”Young said.

To make this myth a reality, the developers at Rancho Santa Fe obscured the history of the area. Builders advertised that the King of Spain had given the land to the former owner of the property, Don Juan Maria Osuna, rather than the reality that it was bequeathed to the Osuna family by the Mexican government.

This allowed future residents to imagine themselves as descendants of Spanish donkeys who ruled over their large estates. “These things are built in these ideals of the suburban ideal,” said Young. “You can have your Spanish fantasy past, but still exist in a homogeneous Anglo neighborhood.”

More than a century later, Rancho Santa Fe remains an unincorporated property administered by the Rancho Santa Fe Association. And locals and real estate agents still refer to the area ruled by the Schutzbund as “The Bund”.

Mike Damron

Janet Lawless-Christ (left) and Mary Bills sit and chat in Bill’s garden in Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., August 11, 2021.

Mary Bills, a Rancho Santa Fe resident, and her friend, Janet Lawless Christ, a local real estate agent, want the community to take further steps to address their racist past.

They stand behind an attempt to change the name of the Rancho Santa Fe government document, which they believe is discriminatory, and encourage people to stop referring to the area as “The Covenant.”

“We just ask that you (the association) bring up this code word that is still sending signals of discrimination – by using these words, by having this document – and people of goodwill when they know something is wrong and themselves don’t change then I think there is a problem, “said Bills.

“I would guess that 80% of the people who live in the Bund don’t understand this … We should know that the Bund had restrictive racial prejudice when it was written. We should acknowledge that. ”

Janet Lawless Christ, Rancho Santa Fe resident

Both Bills and Lawless Christ say they want to start a conversation about a story they believe many people who live in Rancho Santa Fe didn’t even know about it.

“I would guess that 80 percent of the people who live in the covenant still don’t understand,” said Lawless Christ. “We should know that when the Bund was written, it had restrictive racial biases. We should acknowledge that. “

The community is proud of its architectural history. The club’s website talks about Bing Crosby’s famous clambakes at the golf club, but never mentions anything about race restrictions.

“An elitist message is being sent and people are protecting it,” Bills said.

The exclusivity and racial boundaries of the area are still palpable for many. Rancho Santa Fe remains 83% white, according to the US Census.

Get a “second look”

“I still feel that feeling of exclusivity,” said Lisa Montes.

Cristina Kim

Lisa Montes points to her parents’ wedding photo at the Solana Beach Heritage Museum, Aug. 10, 2021.

Montes is a fourth generation daughter of La Colonia or Eden Gardens, the racially segregated community created to house the mostly Mexican-American workers needed to maintain Rancho Santa Fe’s lands. Her uncle worked as a gardener at Rancho Santa Fe and her aunt as a housekeeper.

“Eden Gardens was a racially segregated community. It was designed specifically this way for Mexican Americans, ”said Montes, who is also the museum curator of the Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society and vice president of the La Colonia Community Foundation.

While Rancho Santa Fe was being built into modern Spanish-style villas, the residents of La Colonia first had to live in tents before they finally got the materials to build their own homes.

Growing up, she always heard stories about the racism her family encountered when she left the borders of La Colonia.

Her cousin was prevented from having his hair cut in Solana Beach because of the color of his skin. Another cousin, Robert “Chuckles” Hernandez, was falsely accused of stealing a white man’s radio as a young boy. Montes says a local sheriff’s assistant beat him.

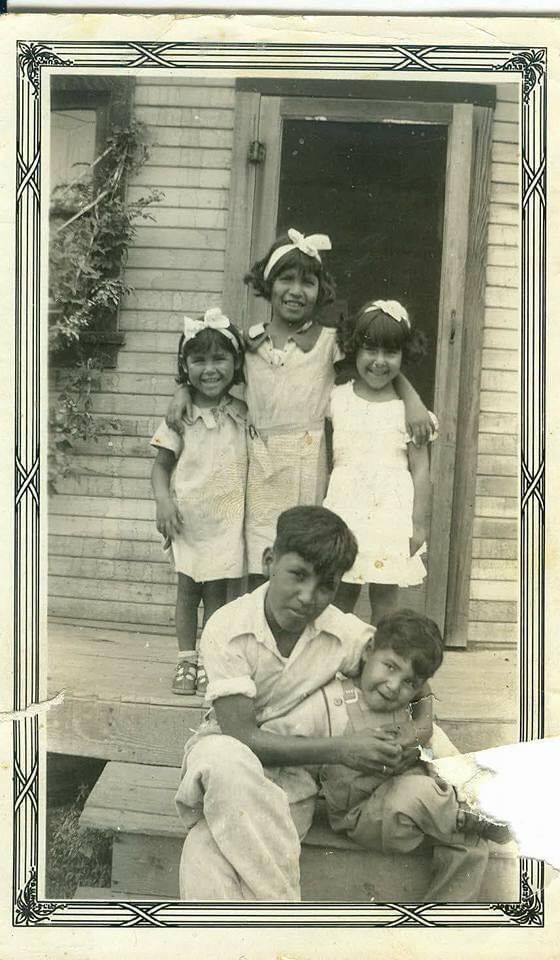

Courtesy Lisa Montes.

Elvira Scott, Virginia Villa, Celia Scott, Eddie Villa and Dickie Scott (left to right) in La Colonia de Eden Gardens in 1936.

Despite these experiences, says Montes, the residents of East Garden formed a tightly knit and vibrant community even as they battled increased gang activity in the 1980s and 90s. But now the community is starting to change.

Money flows into Eden Gardens as property values soar in Solana Beach and near Del Mar. Montes is concerned that the community that made La Colonia so magical is disappearing due to gentrification.

“These are first-class properties now. Before it wasn’t considered prime real estate, it was considered Eden Gardens, you know, less than in terms of properties you want to live in, ”said Montes. “Now they want to pick it up and build their mansions on it.”

Montes understands the neighborhood is changing, but she fears the story of the Mexican Americans who created Eden Gardens will be forgotten. That’s why she keeps history alive through historical tours for local college students and the planning of the annual Dia de Los Muertos event at Eden Gardens.

But while the racial boundaries that surrounded Eden Gardens are rapidly fading, for Montes the barriers around Rancho Santa Fe remain.

“If I went to any of the Rancho Santa Fe boutiques I would take a second look,” said Montes. “And it’s the looks you get from people, that second look like ‘Who are you?’ It’s just something you notice. “

She may live there and even shop there, but she still has to grapple with the haunted places that only white spaces leave behind.

Cristina Kim

Rancho Santa Fe Association Office, Aug 11, 2021.

One way forward

This is the legacy that Bills and Lawless Christ want to address. They asked the Rancho Santa Fe Association to consider their proposal, but they didn’t get much publicity.

In reporting this story, KPBS reached out to several people at Rancho Santa Fe who refused to speak on the matter, including a prominent real estate agent and members of the Rancho Santa Fe Historical Society.

Christy Whalen, the manager of the Rancho Santa Fe Association, told KPBS in a written statement, “All homeowners associations have agreements” and that “if there’s a story here, the Rancho Santa Fe Association is ahead of the curve” by the distance the language in 1973.

She went on to say that “covenant” is a term that means an agreement and has no racial connotation and that even if changes were made, the word covenant should still be used.

Bills and Lawless Christ aren’t surprised by reactions like Whalen’s.

“I’ve heard people say, ‘Just stop stirring the pot.’ In which saucepan do we stir and why do we have to stop stirring the saucepan? We have to keep going, ”said Lawless Christ. “We have not yet reached a place where the word ‘Bund’ has no racially charged meaning. By deleting the word, we are taking a step in the right direction. “

Neither Bills nor Lawless Christ believe that changing their name will eliminate injustice or radically change the community. But they believe that openly acknowledging Rancho Santa Fe’s past will allow it to evolve into a more inclusive place.

Like Lisa Montes ‘quest to preserve Eden Gardens’ unique history amid gentrification, Bills and Christ are waging a similar battle – a battle over what is remembered, who can live where, and why it matters today.

Comments are closed.